Pvt. DeArmond’s Journey to Ft. Freeland

This is the third and final post in a series about Pvt. Thomas DeArmond’s service as a rifleman in America’s Revolutionary War. The first two posts (and this one) are available at https://www.hoosierscientist.com/blog. Your comments are encouraged, but any that are inconsistent with a civil and fact-based discussion of our true Revolutionary War history will be deleted. Please consider reading some of the abundant resources on this topic, a few of which are listed in the comments.

After participating in the British defeat at Saratoga and the famous winter at Valley Forge, Pvt. DeArmond may have fought under Col. Morgan in June 1778 as one of the riflemen who helped harass British troops during their withdrawal from Philadelphia to New York. During that spring and early summer, however, Morgan dispatched some of his riflemen north to aid in the continuing battle of American settlers and militia against British troops and their Iroquois allies. The American victory at Saratoga put an end to large-scale, European-style warfare in upper New York, but many Iroquois remained determined to continue the war, and the British were anxious to assist.

Native Americans were never entirely united except in their desire to maintain control over the lands they occupied. Those who sided with the British or the Americans, and those who remained neutral during the Revolution, did so almost entirely on the basis of what they judged to be their own best interests. Even among the six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora), the Oneida and Tuscarora chose to fight alongside the Americans, while many Onondaga sought to remain neutral.

Significant battles along the northwestern frontier during Pvt. Thomas DeArmond’s service as a rifleman included raids led by Mohawk leader, Thayendanegea (also known as Joseph Brant). These raids began in May of 1778, a few months after the Iroquois had left the Saratoga battlefield. The raids continued through the summer of 1778 and extended as far south as Wyoming, Pennsylvania. The Americans were generally ineffective in stopping the guerrilla-style raiders but mounted strong retaliatory raids against the Iroquois towns of Unadilla and Onaquaga in New York.

Each of these “minor” battles has its own story, sometimes including atrocities, but the example described here is a raid at Fort Freeland in north-central Pennsylvania by 100 British soldiers led by Capt. McDonald and 300 Seneca warriors. It is not clear which battles Pvt. DeArmond might have participated in; however, Fort Freeland is particularly relevant here since it is quite near the location where DeArmond would move his family after his discharge from the Army. When the fort was attacked on July 28, 1779, it was defended by 21 able-bodied men and also occupied by 52 women and children. The battle lasted long enough that the women were called on to help by melting household items to produce bullets. When the outnumbered Americans were forced to surrender, Capt. McDonald offered terms that included safe passage for the women and children and prisoner-of-war status for the surviving adult men. The victors looted and burned the fort, but the militia at nearby Fort Boone had heard the firing and arrived while the Seneca and British were still there. Unaware of the surrender deal, the outnumbered soldiers from Fort Boone renewed the battle, and there were many additional casualties on both sides, including some of the men who had agreed to become prisoners of war.

One of the most controversial letters of the Revolutionary War is George Washington's letter to Major General John Sullivan, dated May 31, 1779, directing him to launch an expedition against “the hostile tribes” of the Iroquois. It states, “The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more....”

Some writers have interpreted this as calling for “genocide,” or the complete elimination of the four Iroquois tribes that were continuing to side with the British. Personally, I’m ready instead to take Washington at his word. I see this as an effort to extend the American victory at Saratoga to include the hostile Iroquois, but with the recognition that the male combatants could not be separated from their families in the same way British and German soldiers were separated. Perhaps Washington intended the new prisoners (including women and children) to be held in some sort of prison camp until the war was over, or perhaps there was no specific plan at all for managing the prisoners. While I continue to respect and admire Washington, I’m frightened to think what would have happened if Sullivan’s Expedition had actually proceeded according to Washington’s instructions.

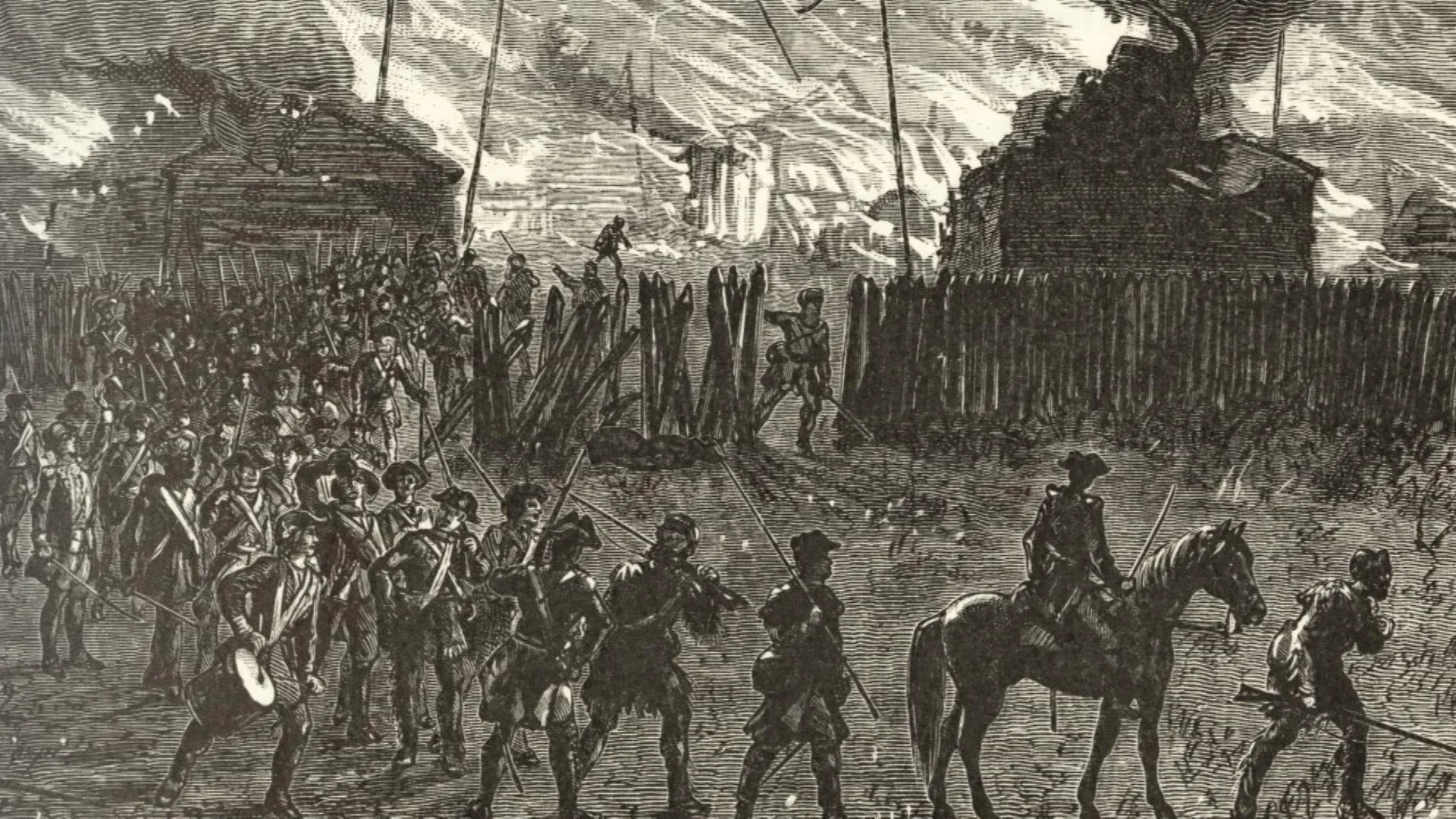

Sullivan gathered over 4000 soldiers for the campaign, including 3 companies of Morgan’s Riflemen. Morgan himself was not part of the expedition, but payroll records show the illiterate DeArmond with his name misspelled “Thomas Dermott.” This was one of the Continental Army’s largest campaigns of the entire War, with 134 flatboats, 1200 pack horses, 700 head of cattle, and 9 artillery pieces. When they attacked the first of their targets, the Delaware village of Chemung, they found it had been hastily abandoned. As they would do at dozens of other villages, the Army proceeded to burn the structures and destroy the crops and food stores. As the Americans were burning fields, 30 Delaware ambushed a group of soldiers and killed six.

During the 107 days Sullivan’s Army was in the field, it faced only one serious effort to stop its advance. At Newtown, they encountered a force of Iroquois, Delaware, and British troops prepared to make a stand from behind a log breastwork. The battle was brief. The British ordered a withdrawal when the commander felt the Americans were going to flank their defenses. The remainder of the Expedition consisted of destroying unoccupied villages and the surrounding crops.

In general, the British were convinced Sullivan’s massive force must be preparing to attack a significant British objective, either Fort Detroit or Fort Niagara, and they were reluctant to commit their forces to defending Iroquois territory. Sullivan’s Expedition yielded almost no prisoners of any sex and relatively few casualties, but it succeeded in destroying almost all of the sophisticated longhouses, gardens, fields, and orchards upon which Iroquois society had long depended. The Iroquois protected their women and children by choosing to evacuate rather than stand and fight a series of unwinnable battles. Over 5000 Iroquois refugees fled to Fort Niagara, where most—but not all—survived the unusually brutal winter of 1779-80 with the limited resources the British could provide. Refugee status was likely much better than becoming prisoners. I continue to believe Pvt. Thomas DeArmond and the rest of the 4000 soldiers who participated in Sullivan’s Expedition were true American patriots and heroes. I also acknowledge that there must have been at least a few among the 4000 American soldiers who would have considered themselves entitled to treat captive Iroquois women and girls in the most brutal ways.

The Expedition kept DeArmond in the Continental Army a few months beyond his three-year enlistment, but he soon returned to his family and farm in Dauphin County. Like many other farmer/soldiers who had just seen the rich fields and orchards that were once occupied by the Iroquois, DeArmond moved westward to a new farm near the old Fort Freeland. By 1783, he and his wife were living on 150 acres of land. They had two additional sons and became leading members of the Warrior Run Presbyterian Church. Thomas DeArmond died in 1816 at the age of 86 and is buried beside his wife in the Warrior Run Church Cemetery. In 1806, the two sons who had stayed to work the farm while their father was serving in the Continental Army moved still further west, travelling by flatboat with their families down the Ohio River to establish farms near what is now Cincinnati.